This week, I’d like to talk about an invasive species: the water hyacinth.

This plant is one of the most problematic invasive species in the entire world. Introduced into warm freshwater, the water hyacinth can explode in population, overwhelming lakes, ponds, and rivers with thick floating mats of vegetation. In fact, the hyacinth will quickly cover the entire surface of invaded bodies of water. A patch of hyacinth can double in size roughly every two to three weeks. This blocks sunlight from entering the water, starves the water of oxygen, and prevents water circulation. This will quickly destroy native plants, removing possible competitors to the hyacinth, and starve fish and other animals. The thick mats, when in rivers, float into navigation markers and flood control structures.

The hyacinth was introduced into North America in 1884, brought to the World Fair in New Orleans, Louisiana. The hyacinth escaped, entering the Mississippi River, causing huge problems for steamboat navigation. I’ll come back to this in a bit.

In Florida, the hyacinth was brought back by a visitor to the World Fair, Mrs WF Fuller. Here’s an article that discusses this in a little more detail:

http://www.dailykos.com/story/2013/11/23/1253952/-Florida-s-Invaders-Water-Hyacinth

https://richesmi.cah.ucf.edu/omeka2/items/show/552

https://richesmi.cah.ucf.edu/omeka2/items/show/449

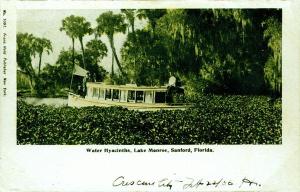

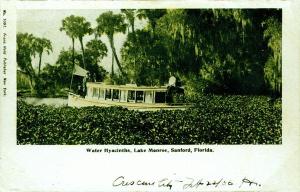

Here are two photos from RICHES, part of the Chase Collection and Sanford Riverfront Collection, respectively. They show hyacinth in Lake Monroe and the St Johns River. The first is circa 1900-1920; the 2nd dates from 1906. You can see how dense the hyacinth can grow. The Daily Kos article, linked above, claims the hyacinth covered some 200 miles of the river within 12 years.

Documents from the FOLA archives show evidence of hyacinth in Lake Apopka as early as the late 1950s, and probably earlier. The documents discuss hyacinth removal programs, seemingly already established at this time. Lake Apopka connects to the St Johns via the Apopka-Beauclair canal, as I discussed earlier. The water hyacinth must have made a long, long journey, through the entire St Johns into the Harris Chain of Lakes, down the canal, and finally into Lake Apopka.

This plant has more significance to the lake, beyond it’s invasive nature, because of the role it’s played in the debates of the origins of the lake’s pollution. One study from the 1960s cited the hyacinth removal program in 1957-1959 as a major source of problematic nutrients for the lake.

https://richesmi.cah.ucf.edu/omeka2/items/show/5501

That’s a newspaper article discussing the report, which was performed by the Florida State Board of Health. The report claims 3 major factors as responsible for the lake’s polluted state: the 1947 hurricane, which uprooted native vegetation, and the shad and hyacinth removal programs in 1957-1959. These last two programs, which aimed at destroying unwanted inhabitants of the lake, failed to remove nutrients because the shad and hyacinth were left to decay in the lake. I should point out this report was disputed in its day.

https://richesmi.cah.ucf.edu/omeka2/items/show/5504

Here’s a memo to the Chief of Fisheries for the Florida Game and Fresh Water Fish Commission, an organization that had been monitoring fishing in Lake Apopka for years (as was its purview). The memo disputes these 3 factors as “major”, considering nutrient inflow from the muck farms, sewage treatment, and citrus industry to be much more decisive in causing the lake’s pollution.

This same argument would be repeated 50 years later in the 1990s. Scientists from the University of Florida claimed these exact same three factors as causing the pollution, and disputed claims that the muck farm buyouts would do anything to help restore the lake.

Click to access AltStableStates.pdf

Here’s the study in question. The basic argument is: the thick mats of hyacinth prevented major wave action from occurring in the broad, shallow lake. After the hyacinth were killed in ’47 and ’59, the lake became “turbid” and sediment was easily stirred up by wind and wave action, preventing aquatic vegetation from becoming firmly rooted. This, and not nutrient loading, was Lake Apopka’s problem.

The Friends of Lake Apopka, of course, disagreed. The buy-out was able to proceed. I’ll be able to show the rebuttals to the UF argument from the 1990s at a later time.

Is removal of invasive species always a good thing?

In fact, efforts had been made in the 1980s to study reintroducing the hyacinth as a potential clean-up method for Lake Apopka! The hyacinth is obviously adept at removing nutrients from water, and is successfully used to treat sewage waste.

http://articles.orlandosentinel.com/1985-10-21/news/0340040260_1_lake-apopka-hyacinths-rivers-and-lakes

I think this is a fascinating plant that really illustrates how complex environmental science can be. Archiving can help reveal the nature of these debates, and show they are sometimes never really settled.

PS: The hyacinth in the Mississippi River? A Lousiana lawmaker in 1910, spurred by the New Foods Society, introduced a novel solution to this invasive species: introduce the hippopotamus to the waters of the Mississippi River. The hippo, it was assumed, would devour the floating vegetation, and the hippo in turn could be slaughtered and sold for its meat. A strange idea, considering the hyacinth is native to South America, not Africa. The bill failed to pass by one vote. The idea of the hippopotamus roaming the shores of the Mississippi is a terrifying one.