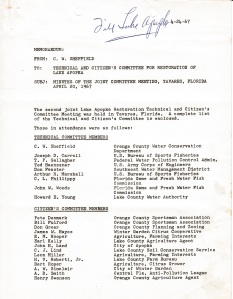

In 1985 Governor Bob Graham formed the Lake Apopka Restoration Council. Like its predecessor of the 60s, the Lake Apopka Technical Committee sought to determine water quality standards for the lake, and investigate potential routes towards restoration.

After meeting in March 1986, the Council determined a set of standards that would make the lake suitable for recreation and fishing. The archives, unfortunately, don’t have any documents from 1986 to 1989, other than the Council’s 1986 statement of intent.

The FOLA timeline states that the St Johns River Management District, responsible for Lake Apopka, began initiating restoration projects that had been recommended by the Council at this time. One of these projects was what would become the Marsh Flow-Way.

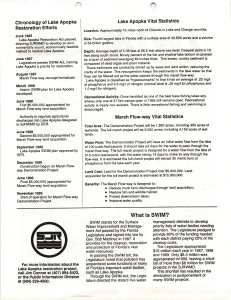

In 1987 SWIM was passed, designating Lake Apopka as a priority body of water. SWIM would increase funding for the lake’s restoration, and in 1988 the Flow-way Pilot Project was begun.

The SJRWMD purchased 5,000 acres of land on the northwest corner of the lake, and construction of the project began December, 1989.

Here’s part of a SWIM factsheet discussing the flow-way. The flow-way is essentially a wetland, using natural processes to remove sediment and phosphorus from the lake. The vegetation slows incoming sediment and helps it to settle to the bottom. The vegetation also blocks the wind, preventing it from churning up the water and reintroducing the sediment into the water column. This is one of the major problems for the lake itself – with such a large surface area and shallow depth, wind has an enormous effect on the lake’s bottom. Vegetation also plays a role in nutrient uptake, directly absorbing nutrients from the water.

Water is pumped through the flow-way and travels through a series of cells:

I think the flow-way should also be understood in contrast to other biological nutrient removal processes that use non-native species. The flow-way, though manmade, uses native wetland species. I’ve mentioned the usage of hyacinth, for example, in nutrient removal systems. As I showed you earlier, this is a highly invasive species with a serious potential to escape any system it’s confined to.

Water began moving through the flow-way in 1990:

This “experimental operation” would be finished in 1997, as the farm buy-outs were gathering steam. A full-size plan would be drawn up. In 2001 the Flow-way began phase 1 of its operation. The flow-way treats around half of the volume of the lake yearly, but this is highly variable.

In this photo, north is to the right. You can see the flow-way’s cells in the top half of the photo, emptying into Lake Apopka. Notice the contrast between the blue water leaving the flowway and the green “soup” of the rest of the lake.

The flow-way is important because simply halting discharge of nutrients into the lake isn’t enough to restore it. The nutrients must be removed to help the lake back into more stable conditions. From 2003 to 2009 the flow-way removed 37,000 lbs of phosphorus, along with 62 million pounds of loose sediment.